However, Paul MacCready's story also shows how much untapped potential there tends to be in people. If he hadn't been motivated by his debts, perhaps he would have just done his regular job well and built a few model airplanes with his children in his spare time.

The extraordinary story of how the first BMW 3 Series Touring came about is similar. Max Reisböck had a problem in 1984: his employer's brand strategy did not suit his family's needs as BMW did deliberately not have a hatchback in its model catalog, and the notchback version of the 3 Series was too small for his growing family. So, the trained car body maker, who had already been working in prototype construction at BMW for several years, quickly turned an E30 notchback saloon into the first BMW 3 Series Touring1 in his spare time. Unfortunately, this remarkable achievement did not solve his problem in the short run. When his prototype was presented at the headquarters in Munich, the then Chairman of the Board of Management, Eberhard von Kuehnheim, and his Head of Development, Wolfgang Reitzle, immediately recognized the potential of this model and ordered appropriate secrecy for further development until it was ready for series production: “This car will not leave the company grounds.”2

In Lean Management, there are seven classic types of waste. These seven are frequently, and as Paul MacCready and Max Reisböck's examples show, quite rightfully, supplemented by an eighth type of waste: the unused potential of employees. Harnessing human potential and creativity for continuous improvement is a key principle of Lean Management. In this respect, this eighth type of waste underlies and complements the other seven.

The rise of Toyota after the Second World War is inextricably linked with the name Taiichi Ohno. He was instrumental in shaping and developing the Toyota Production System. What is understood today as Lean Manufacturing and more general as Lean Management can largely be traced back to him. Toyota succeeded in significantly increasing productivity and thus could not only catch up with its American competitors from Detroit but overtake them. The concepts and methods of Lean Management spread in the manufacturing industry and many other areas and sectors, including IT, where the “Manifesto for Agile Software Development”3 can be understood as applying Lean Management principles to the software development process.

In many factories, overproduction of semi-finished and finished products was common. These buffers allow quality fluctuations during production (and in the supply chain) to be compensated for to a certain extent and to avoid effects on quality and delivery dates. Because these buffers are so practical and seemingly indispensable, this type of waste is often not even recognized as such. Nevertheless, the hidden costs of inventory, storage space, and transportation are hard to underestimate.

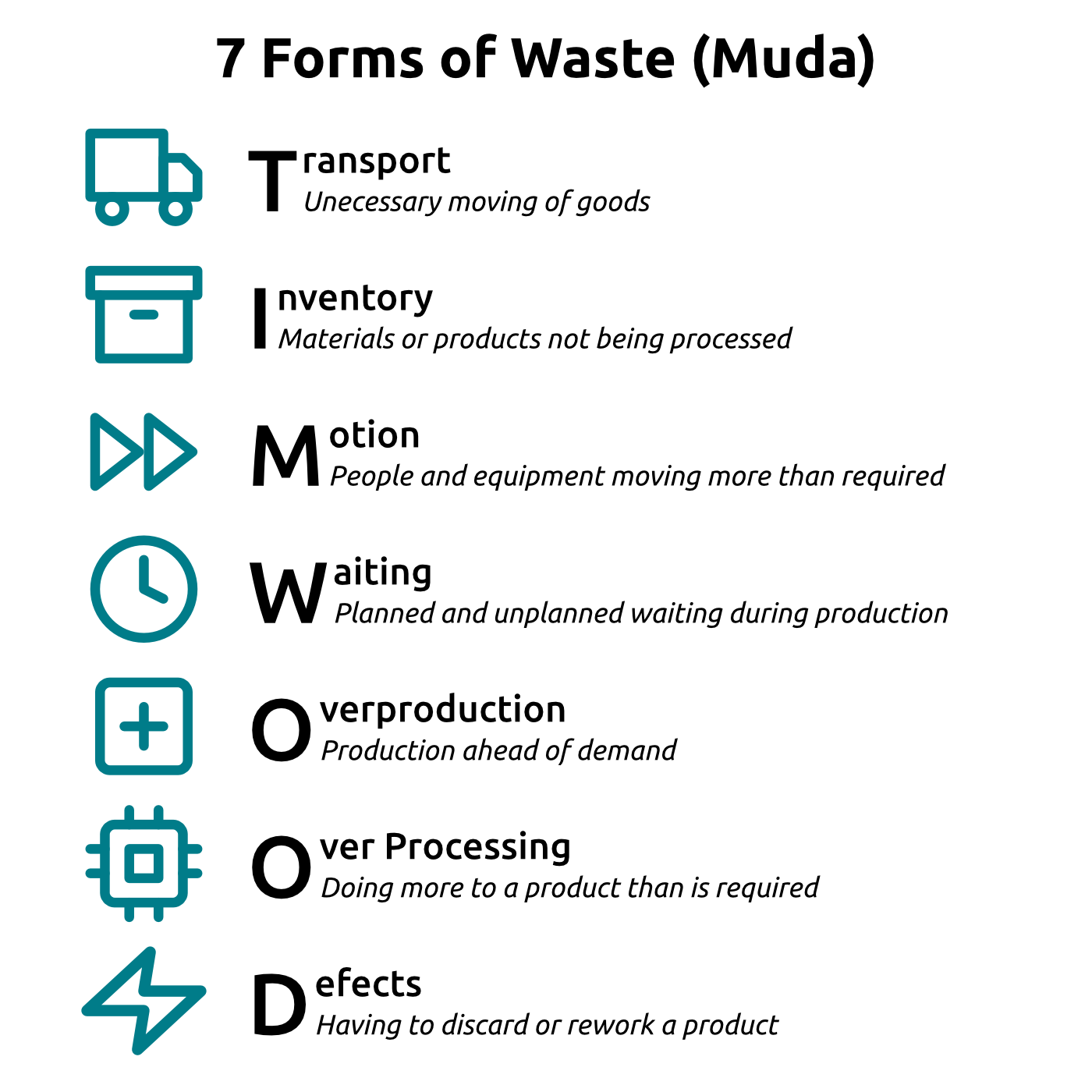

A central element of Lean Management is, therefore, the elimination of waste. This means avoiding wasteful activities, i.e., activities that do not generate any value, which is a better translation of the Japanese term muda than waste. Traditionally, there are seven types of muda, as shown in this graphic:

Those seven types all relate to processes. They describe symptoms of weaknesses in work processes, the causes of which must be found and eliminated. Continuous process improvement, also known under the Japanese term Kaizen, is an essential element of the Toyota Production System. In contrast to the very Tayloristic view that prevailed at the time, however, this continuous improvement in Lean Management is not reserved for the manager but is the task of the “ordinary” workers—a small but significant difference.

Avoiding the seven types of waste requires the creativity of everyone involved in these processes. Managers' central task is to empower these previously “ordinary” workers and train them to do so. In essence, Taiichi Ohno was concerned with developing this untapped human potential.

To emphasize this, unused human potential or unused creativity is often regarded as the eighth type of waste. Rightly so, because organizations are still run like machines, and people in them are treated like cogs whose skills are not in demand beyond their current job description. This eighth type of waste undoubtedly has a different character than the other seven, but utilizing creative potential is so crucial in Lean Management that adding this eighth type of waste to the seven classic types makes a lot of sense.

It pays off when human resources finally become human potential.

Respect for People

A lot can be learned from Lean Management: understanding the value for the customer, identifying the value stream, optimizing the flow through the system to avoid unnecessary effort, and, last but not least, ensuring continuous improvement. However, Lean Management is not just about using different and better methods but also about a different management culture. Respect for people is often forgotten as an essential pillar of the Toyota Way4. People are at the heart of Lean Management. Therefore, the central management task is to “empower instead of instruct.” This principle should be disseminated as intensively as the well-known methods of Lean Management.

Toyota's extremely successful turnaround cannot be explained simply by a brilliant engineer's invention and introduction of a few groundbreaking concepts, as the heroic story of Taiichi Ohno might suggest at first glance. The foundation of this transformation was a change in management culture that put people and their creativity front and center. The individual worker was no longer a passively affected object but became an actively shaping subject, as Taiichi Ohno clearly expressed5: “Standards should not be forced down from above but rather set by the production workers themselves.”

Yoshihito Wakamatsu, who worked directly under Taiichi Ohno for many years, reported the following anecdote, which shows how serious Taiichi Ohno was about this empowerment6: During a visit to a Toyota plant, Ohno was accompanied by a manager from another company. This manager noticed some things that could have been improved in the implementation of the Toyota Production System and asked Ohno why he had not corrected them immediately. Ohno's answer was:

I am being patient. I cannot use my authority to force them to do what I want them to do. It would not lead to good quality products. What we must do is to persistently seek understanding from the shop floor workers by persuading them of the true virtues of the Toyota System. After all, manufacturing is essentially a human development that depends heavily on how we teach our workers.

This response is an excellent example of a vital attitude of humane leadership, which is less about correcting, guiding, or instructing but instead means empowering. Correcting processes from the outside would only cure the symptoms in the short term but would not result in a healthy organization.

This empowerment makes the individual worker an active shaper of continuous improvement, and the resulting broad impact made a decisive difference in Toyota's transformation. This needs to be recalled today when agile transformations in many companies are reduced to introducing blueprints and frameworks.

Therefore, the 'e' in Lean and Agile stands for empowerment, or at least it should. Unfortunately, both philosophies, which are related and build on each other, are often reduced to visible practices, methods, and tools. However, anyone who introduces these without simultaneously working on the foundations of the human image and leadership attitude is building on sand. Richard Feynman aptly describes the result of this reduction as a “cargo cult,” i.e., the beautiful imitation (in his case of scientific work) without a deeper understanding of the purpose and the bigger picture7:

In the South Seas, there is a cargo cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they've arranged to imitate things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas--he's the controller--and they wait for the airplanes to land. They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they're missing something essential because the planes don't land.

The self-organizing team is at the heart of Agile. It is explicitly called for in the principles behind the Manifesto for Agile Software Development8: “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.” And so that there is no doubt about the leadership attitude that goes hand in hand with this, it also says: “Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.” There is no such thing as an agile team without self-organization and empowerment, even if frameworks or blueprints have been copied and rolled out exemplary and the processes are celebrated ideally. As long as Agile is imposed on people from above without the necessary empowerment and the necessary change of leadership attitude, it will end in a soulless cargo cult.

As with Toyota and Lean Management, the key to a successful agile transformation lies less in choosing or designing the right frameworks, processes, methods, or tools, an exercise that, unfortunately, is very appealing to managers and consultants, and much more in empowerment and self-organization. Employees must be seen as active subjects of the transformation and, ultimately, of their organization instead of being degraded to passive objects and mere target groups of intrusive change management measures.

Super Chicken

The human element in a digital world is not just an individual matter but a question of culture and organization. A group of super talents does not make a good team. On the contrary, many strong egos can become dysfunctional as a team. This applies not only to soccer teams but also to chickens.

In her TED talk “Forget the pecking order at work”9, Margaret Heffernan reports on an impressive experiment. William Muir from Purdue University investigated the productivity of chickens, which can be measured simply in the number of eggs. He selected only the top performers for the first group and ensured that only the best of these super chickens reproduced. This was contrasted with a second group of average chickens that were not further selected or influenced. After six generations, the chickens in this control group were well-fed and fully feathered, and their productivity had increased slightly. Contrary to naïve expectations, the situation was somewhat different in the group of super chickens: all but three were dead—pecked to death by the others.

The explanation for the experiment's surprising outcome at first glance is quite bland. The higher productivity of the super chickens went hand in hand with their ability to assert themselves against others at the food bowl. The targeted selection of precisely these individuals reinforced this characteristic of aggression and competitive behavior from generation to generation. However, those who fight each other may prevail as individuals but waste energy as a group. The extreme focus on individual excellence encourages competition and dysfunctional teams. Unfortunately, companies, school systems, and entire societies are built on this principle.

Google also realized that superstars alone do not make a team. As part of “Project Aristotle,” the company investigated what turns a group of people into an effective team. The most important element by far turned out to be psychological safety10. Effective teams have a high degree of safety, so members dare to speak their minds openly and take risks. This is the crucial ingredient that makes the whole more than the sum of its parts--and, therefore, fostering psychological safety is an essential leadership task. It takes this sense of security and trust to generate excellent ideas, as Margaret Heffernan explained in her TED talk with the following beautiful analogy11:

And that's how good ideas turn into great ideas because no idea is born fully formed. It emerges a little bit as a child is born, kind of messy and confused but full of possibilities. And it's only through the generous contribution, faith and challenge that they achieve their potential.

Table of Contents

The links lead to the parts that are already published here on Substack.

The Eighth Type of Waste

Respect for People

Super Chicken

Six Theses for New Leadership

Manifesto for Humane Leadership

Human Potential, Not Human Resources

Diversity and Dissent

Leading with Purpose and Trust

Network and hierarchy

Encounter at Eye Level

The Art of Ambidexterity

The 14 Principles Behind the Manifesto

People are at the Center

Start With Self-Care

Strengthen Strengths

Leadership Means Relationship

Context Not Control

Gardener Not Chess Master

Principles Not Rules

Less is More

Questions Not Answers

Trust Is the Foundation

Safety Not Fear

He Who Says A Does Not Have to Say B

Integrity Over Charisma

Disturbing the Comfort Zone

Get to Work!

Leading by Example

Incitement to Rebellion

Set Priorities

Enduring Dissonance

Doing Your Best

The next chapter will follow next Friday. In case you want to read on as soon as possible, the book is available on Amazon in many countries as hardcover, paperback, and for your Kindle. (also on Leanpub). And all my German readers can get the German edition in every book store.

Wolfram Nickel, “BMW 3er Touring E30: Und plötzlich waren Kombis cool - WELT,” DIE WELT, September 27, 2017, https://www.welt.de/motor/fahrberichte-tests/oldtimer/article168818064/Und-ploetzlich-waren-Kombis-cool.html.

Max Reisböck himself tells this story best in this official BMW video (in German) Max Reisböck BMWstory. Erfinder des BMW 3er Touring., 2015,

Beck et al., “Manifesto for Agile Software Development.”

Toyota Motor Corporation, “Toyota Way 2020 / Toyota Code of Conduct,” Toyota Motor Corporation Official Global Website, 2020, https://global.toyota/en/company/vision-and-philosophy/toyotaway_code-of-conduct/index.html

Taiichi Ohno, Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production (CRC Press, 1988), 98.

Yoshihito Wakamatsu, The Toyota Mindset: The Ten Commandments of Taiichi Ohno (Enna Products Corporation, 2017).

Richard Feynman, “Cargo Cult Science,” Engineering and Science 37, no. 7 (June 1974): 10--13.

Beck et al., “Manifesto for Agile Software Development,” https://agilemanifesto.org

Margaret Heffernan, “Forget the Pecking Order at Work,” https://www.ted.com/talks/margaret_heffernan_forget_the_pecking_order_at_work

Charles Duhigg, “What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team,” The New York Times, February 25, 2016, sec. Magazine, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

Heffernan, “Forget the Pecking Order at Work.”