Leadership Beyond Hierarchy

In last week’s post, we arrived at the central chapter of my book with the six theses of the “Manifesto for Humane Leadership.” Here come now the next two theses.

Leading with Purpose and Trust

The most fundamental task of leadership is to ensure a common direction. With that in mind, leadership is particularly crucial for agile organizations. Agility requires alignment to make self-organizing teams effective. If this orientation is missing, agility becomes arbitrary, and, in the worst case, you end up running around in circles.

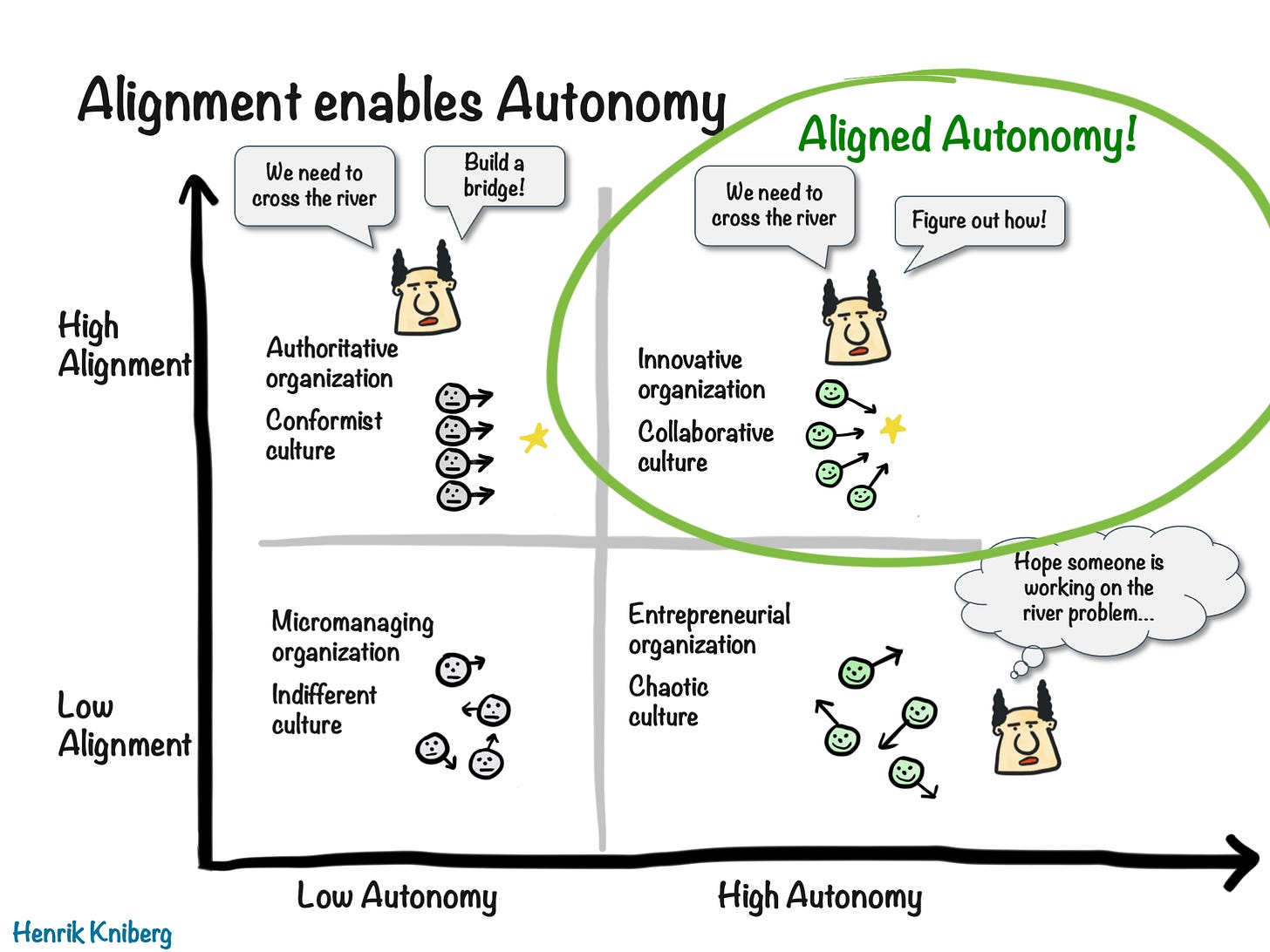

Self-organizing teams are a core element of agility. The remarkable flexibility and customer focus of agile organizations result from the speed of decentralized decision-making. As Henrik Kniberg shows in the above illustration, autonomy requires alignment so everyone knows and works towards the common goal.

Therefore, the question is not whether but how leadership should provide orientation today. On the one hand, there is the more traditional top-down management approach through policies and detailed instructions. On the other hand, leadership can also guide by fostering a shared vision and a joint mission and trusting in the inherently motivated individuals willing to make the best possible contribution. That is meant with “Purpose and trust over command and control,” the third thesis of the Manifesto for Humane Leadership.

A key characteristic of knowledge work is that knowledge workers are no longer unskilled and require a skillful manager to make their workforce productive, as was the case at the time of Frederick Winslow Taylor. They own their means of production regarding their knowledge, experience, and skills. Consequently, knowledge workers must be led at eye level (see Section “Species-Appropriate Keeping of Knowledge Workers”).

Self-organizing, agile teams are only a special case of the more general question of how to manage knowledge workers. Peter Drucker's answer is relatively simple: knowledge workers must be managed as if they were volunteers otherwise financially secure. With that, leading with pressure and fear is no longer viable. The only option is to offer a purpose and a vision to which as many people as possible want to contribute voluntarily because they are attracted to it.

In this sense, the Manifesto for Humane Leadership's third thesis emphasizes purpose and trust over command and control. Yet, the theses are meant to give a direction, and at the very end of the Manifesto, it is stated that both sides of the theses are important. But after the considerations just made, do command and control still have a raison d'être today? Shouldn't it read: “Purpose and trust instead of command and control”?

A boss who moves the pawns across the field like a chess master without giving any further context should hopefully be encountered less and less today. On the other end of the spectrum, fully purpose-driven, visionary leadership and a mature culture of trust, in which everyone does their best to make the vision a reality, is more an aspirational ideal than the reality. In practice, there will be all sorts of graduations between those book ends; thus, there is still some need for command and control. But that should not serve as an excuse not to try hard to avoid it and to come even closer to the ideal.

Network and Hierarchy

Hierarchy has advantages when organizing a well-known business model as efficiently as possible according to defined processes and roles. However, more is needed to achieve long-term and sustainable success. In addition to this hierarchy, designed for the stability and efficiency of today's business, there also needs to be a component responsible for change, improvement, the new, and ultimately, the business of tomorrow.

Traditionally, this task falls to strategy departments, and their means of choice are dedicated change programs and task forces. These approaches have in common that those changes become temporary parts of the hierarchy, and familiar management methods are used to steer them. Those traditional change management methods work well for changes with clear objectives, e.g., introducing a new CRM system or remuneration model. Yet, the basic assumption here is that change is the exception rather than the rule, and strategic decisions are the task of a few strategists and top management.

However, in a world becoming increasingly volatile and markets becoming ever faster, thus making change constant, these traditional centralized change processes fail due to their inherent sluggishness. In such a fast-paced environment, change must become the second nature of the organization, the second operating system, as John Kotter states:1

We cannot ignore the daily demands of running a company, which traditional hierarchies and managerial processes can still do very well. What they do not do well is identify the most important hazards and opportunities early enough, formulate creative strategic initiatives nimbly enough, and implement them fast enough.

The network complements the hierarchy as the first and dominant operating system. The basic idea of this network is to recruit an army of volunteers from all over the hierarchy. They work continuously on change and improvement in small, loosely linked initiatives. They share a strong sense of purpose, a common understanding of the need for change, and a strong sense of urgency. New initiatives and directions will emerge faster within this loose strategic alignment framework, and opportunities will be exploited more quickly.2

Traditional managers of the first operating system, the hierarchy, have an essential role to play. In addition to their primary job as managers of day-to-day business, they must ensure that the network thrives and that the people's contributions to it are equally valued. Leadership in this network is based on purpose and trust rather than command and control (see previous section). The activities in the network require a strong shared sense of purpose and a shared vision to which people can wholeheartedly say yes and to which they happily contribute their time and labor. However, for people to engage in this network alongside their work in the hierarchy, they need permission and the freedom to work on change and improvement. It does not have to be the well-known 20 percent rule at Google, but leadership has to frame explicitly the expectation and the boundary conditions. The key ingredient, however, is trust. Without hierarchical power, only trust can hold this network together and make collaboration productive and effective.

This second operating system, the network, is a meritocracy, as we know it in open-source software development, from Wikipedia and companies such as RedHat3. The task of leadership is to balance both operating systems, the hierarchy and the network. Coming from the first and established operating system of hierarchy, this means strengthening the already existing more or less informal networks in the organization through permission, freedom, trust, and patience. That is why the fourth thesis in the Manifesto for Humane Leadership is “Contributions to networks over positions in hierarchies.”

Table of Contents

The links lead to the parts that are already published here on Substack.

Leading with Purpose and Trust

Network and hierarchy

Encounter at Eye Level

The Art of Ambidexterity

The 14 Principles Behind the Manifesto

People are at the Center

Start With Self-Care

Strengthen Strengths

Leadership Means Relationship

Context Not Control

Gardener Not Chess Master

Principles Not Rules

Less is More

Questions Not Answers

Trust Is the Foundation

Safety Not Fear

He Who Says A Does Not Have to Say B

Integrity Over Charisma

Disturbing the Comfort Zone

Get to Work!

Leading by Example

Incitement to Rebellion

Set Priorities

Enduring Dissonance

Doing Your Best

The next chapter will follow next Friday. In case you want to read on as soon as possible, the book is available on Amazon in many countries as hardcover, paperback, and for your Kindle. (also on Leanpub). And all my German readers can get the German edition in every book store.

John P. Kotter, “Accelerate!,” Harvard Business Review, November 1, 2012, https://hbr.org/2012/11/accelerate.

Kotter.

Jim Whitehurst, The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance* (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2015)