The Insidious Poison of Excessive Regulation

How our tendency to make things more and more complicated over time ultimately causes societies and organizations to collapse.

We are inclined to make our life complicated. This is partly because we tend to solve problems by adding something, rather than eliminating something, even if removing would clearly be a better solution. This tendency was demonstrated very impressively by (Adams et al., 2021) in a series of experiments.

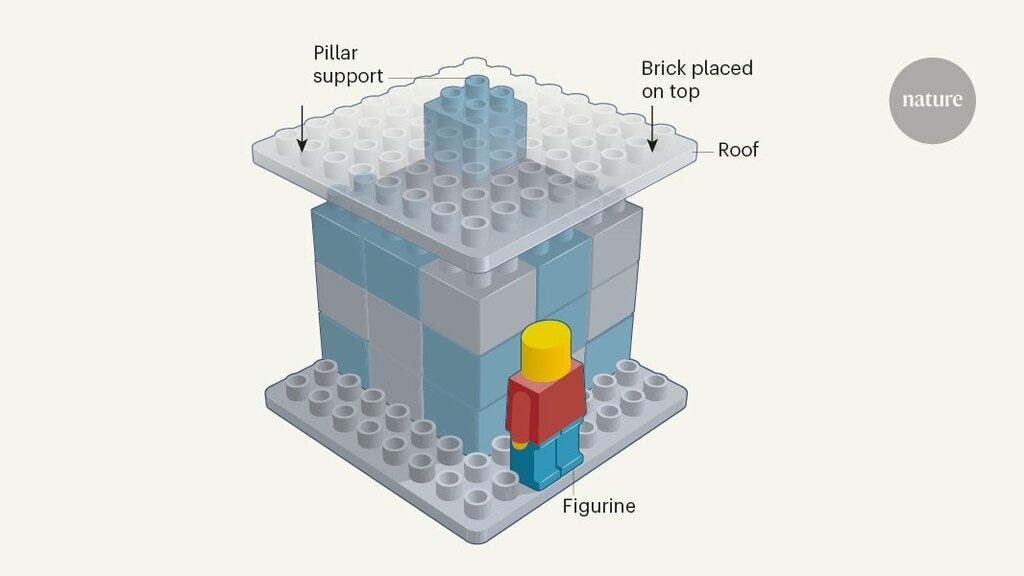

In one of these experiments, for instance, participants had the task of improving the stability of a structure made of building blocks so that in the end the roof would support a heavy brick (see illustration). The participants were to receive one dollar if they succeeded, but each additional brick they used cost 10 cents. Since the roof initially rested on a single small brick well off the center of gravity, participants usually just added more bricks to stabilize the roof. However, it would have been much easier and more profitable to remove the single brick, allowing the roof to lie stably on the rest of the structure.

Why make it simple when you can make it complicated? This mantra seems to guide us not only in such fairly innocuous experiments. Especially when it comes to the regulation of social coexistence or the regulation of work in large corporations, we fall into this trap in abundance.

Over time, societies then tend to become more and more complex and gradually lose their resilience as a result. They solve problems by constantly increasing complexity. Apart from the rather unpleasant singularity of a collapse, however, they have no mechanism at their disposal to reduce this complexity again. At the peak of this development, the society only provides for the complexity it has created itself and lacks the resources to deal with existential threats. What actually causes things to overflow can be very different—a drought, an epidemic, an uprising—but ultimately it doesn't matter. The society collapses as a result, suddenly alleviating the excess of complexity.

This is how Greg McKeown summarizes the main argument of Joseph Tainter's 1990 book “The Collapse of Complex Societies” in Tim Ferriss' podcast. As an anthropologist and historian, Tainter relates his insights to (ancient) societies such as the Maya or the Western Roman Empire, but it is easy to apply them to modern corporations and other bureaucracies. Every company was once a lean and agile start-up. With success and growth, the problems grew, and each solution led to more processes, roles, and guidelines. In the beginning, these rules had great value in containing the chaos. However, the marginal utility of increased complexity quickly diminishes, and you end up with travel expense policies that have recently been facilitated by ChatGPT. Spot the error.

The marginal return on investment in complexity accordingly deteriorates, at first gradually, then with accelerated force. At this point, a complex society reaches the phase where it becomes increasingly vulnerable to collapse.

Joseph Tainter

The British Colonial Office is a good example of this effect (Parkinson, 1955). It was an independent department of the British administration responsible for the administration of the British colonies from 1854 to 1966. The Colonial Office had the most civil servants when it was integrated into the Foreign Office in 1968 due to a lack of colonies to administer. The institution was not very productive, but very busy—apparently mainly with taking care of the self-created complexity.

Not many organizations reach this terminal stage, in which the futile preoccupation with internal processes has completely displaced value creation. An underestimated competitor, a misjudged new technology or something similar leads much earlier to deep cuts and a fresh start, or sometimes to a complete breakdown. Those who want to prevent this should not only be vigilant against these external threats, but must also ensure that the organization remains lean and thus responsive by consistently counteracting the calcification caused by over-regulation.

References

Adams, G. S., Converse, B. A., Hales, A. H., & Klotz, L. E. (2021). People systematically overlook subtractive changes. Nature, 592(7853), 258 - 261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021 - 03380-y

Meyvis, T., & Yoon, H. (2021). Adding is favored over subtracting in problem solving. Nature, 592(7853), 189 - 190. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021 - 00592-0

Parkinson, C. N. (1955). Parkinson's Law. The Economist, 177(5856), 635 - 637. https://www.economist.com/news/1955/11/19/parkinsons-law

Tainter, J. A. (1990). The collapse of complex societies. Cambridge university press. (mentioned in the podcast by Tim Ferris #786 from approx. minute 50:00)