Busy Is Not Productive

Less rules lead to more engagement and better results. Yet the rules and regulations in organizations grow like weeds year after year. A psychological bias might explain that conundrum.

Principles Not Rules

Lenin made the unfortunately not entirely unfounded observation: “Revolution in Germany? It'll never work; when those Germans want to storm a train station, they'll buy a platform ticket!”

Everything has to be in order here in good old Germany.

That's why lawn edges are so popular in Germany. And that's why the myth persists that most of the world's tax literature concerns German tax law. We are well known and appreciated for our conscientiousness and sense of order, even if we occasionally overdo it. Our relationship with creative chaos is strained, to put it mildly.

Of course, there are always good reasons for another rule, a new instruction, or a new process. After all, every eventuality must be considered, every special case regulated, and every abuse prevented.

Where would we end up otherwise?

Good question. That's why the Dutch traffic planner Hans Monderman went and looked, for example, at the busiest intersection in Drachten, where two two-lane main roads meet. Every day, 22,000 cars, 5,000 cyclists, and numerous pedestrians pass this crossing (as of 2005).1 Of course, rules, signs, markings, traffic lights, and a clear spatial separation of cars, cyclists, and pedestrians are needed. Everything must be regulated. However, when we treat people like children, they behave like children, or in the words of Hans Monderman: “When you treat people like idiots, they will behave like idiots.”2

This overregulation is unnecessary, as Monderman proved with his shared space concept. No cycle lanes, road markings, right-of-way signs, traffic lights, and not even sidewalks bring order to the chaos. Hans Monderman liked to demonstrate how well this works by walking backward with his eyes closed across one of “his” intersections.3

Where rigid rules no longer regulate coexistence, confusion reigns. That is precisely the goal because now, people have to think and communicate. There is much more eye contact, and everyone pays more attention to other people instead of traffic lights and their own right of way. This concept has led not only in Drachten but also in various other cities with the shared space concept to lower speeds and, as a result, to a better flow of traffic and significantly fewer accidents, for example, in the Danish town of Christianfield, where fatal accidents fell from three to zero per year following the removal of traffic lights and signs. In the UK, several cities removed the center line on the road, and a study found that 35% fewer accidents occurred.4

Let's focus more on shared values and fundamental principles not only on the streets but also in our organizations. Instead of a plethora of rules, let's trust the people and their good judgment, as Laszlo Bock, formerly Senior Vice President of People Operations at Google, aptly points out:5

Give people slightly more trust, freedom, and authority than you are comfortable giving them. If you're not nervous, you haven't given them enough.

Less is More

Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away. This ideal crafted by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry reveals some potential for refinement in public administration and large corporations. Wherever many people collaborate, rules grow wildly and processes become more complicated.

What happens to the administration when there is less actual work? Cyril Northcote Parkinson asked himself this question. The subject of his investigation was the British Colonial Office, an independent department of the British administration responsible for the administration of the British colonies from 1854 to 1968. Parkinson found that the staff grew regardless of the amount of work; the Colonial Office had the most officials when integrated into the Foreign Office in 1968 due to a lack of colonies to administer. The organization was busy with itself but was not very productive. Parkinson summarized this observation in his law on the growth of bureaucracy:6

Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.

Simplification is not the sweet spot for public administration and large corporations. Yet, less is more. Bauhaus architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe used this famous motto to describe his art. His colleague Richard Buckminster Fuller took a similar view, although he referred to the functional aspects: “Doing more with less.” What sounds so simple, however, is arduous work.

Less is more—especially more work. Not only in architecture. The French mathematician Blaise Pascal apologized for his linguistic overabundance in 1656: “I have only made this letter longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter.”7 His Hungarian colleague Paul Erdős, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, believed in “The Book,” a book of God, which, in his opinion, contains all the short, elegant, and perfect mathematical proofs.8

So if these great thinkers and artists agree that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, as Leonardo da Vinci so aptly put it, how does this cancerous growth of public administrations such as the British Colonial Office and its excessive bureaucracy come about? This phenomenon, which can be observed in an almost identical way in large corporations that have grown over decades, regularly results in rather unsuccessful attempts to reduce bureaucracy.

Perhaps we busy knowledge workers are just like Blaise Pascal; we simply don't have time to streamline our processes. However, the cause of this complication might lie much deeper in our human psyche. When searching for solutions, we primarily prefer to add new elements instead of removing parts, even if the latter would be significantly more efficient or cheaper. At least, that is what research results published in the journal “Nature” suggest.9

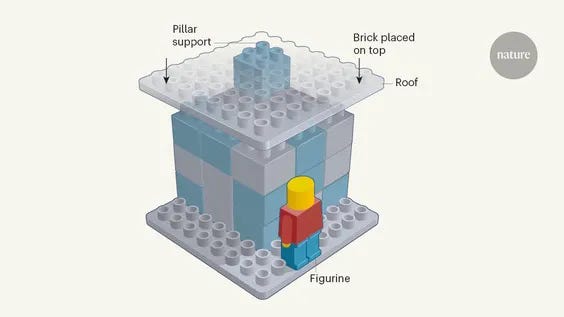

In one experiment, participants were tasked with improving the stability of a LEGO building so that the roof would ultimately support a heavy load put onto it. Participants would receive a dollar if they succeeded, but each additional Lego brick used to stabilize the building cost 10 cents. Since the roof initially rested on a single LEGO brick far off the center, most participants added more bricks to stabilize the roof and support the heavy load. However, it would have been much easier and more profitable to remove the single stone at the edge of the roof, allowing it to rest stably on the rest of the structure.

Removing things doesn't seem to suit us. We prefer to do more of the same. And if that doesn't help, then we do even more. "Having lost sight of our goals, we redoubled our efforts," Mark Twain aptly observed. This universal human tendency combined with German thoroughness also explains the extensive German tax legislation and the finely chiseled travel expense guidelines in our companies.

Bureaucracy was also rampant at FAVI, a French die-casting manufacturer. One of the rules was that if a worker wanted a new pair of gloves from the warehouse, he had to show his supervisor the old pair and then receive written confirmation from him, which the worker had to hand in at the warehouse to get a new pair.

When Jean François Zobrist found a worker waiting outside the warehouse during a factory tour, he did the math and found out that this worker was operating a machine that cost 600 francs per hour, or ten francs per minute. Since the whole process of issuing new gloves took ten minutes, during which the machine was idle, the gloves, worth 5.80 francs, cost the company an additional 100 francs through this control mechanism.10

So Jean François Zobrist abolished these and many other rules and organized FAVI into mini-factories of 15–35 employees, who made all decisions for their respective customers (including the previously centralized functions of Sales, Planning, Engineering, HR, etc.). Here, too, fewer (uniform) rules did not lead to the feared chaos but to more personal responsibility and self-organization. The success of this transformation was remarkable: FAVI subsequently managed to grow from 80 to over 500 employees and continued to produce profitably in Europe with its above-average wages, where other suppliers had long since relocated production to the Far East.11

Table of Contents

All links lead to the parts that are already published here on Substack.

The 14 Principles Behind the Manifesto

Principles Not Rules

Less is More

Questions Not Answers

Trust Is the Foundation

Safety Not Fear

He Who Says A Does Not Have to Say B

Integrity Over Charisma

Disturbing the Comfort Zone

Get to Work!

Leading by Example

Incitement to Rebellion

Set Priorities

Enduring Dissonance

Doing Your Best

The next chapter will follow next Friday. In case you want to read on as soon as possible, the book is available on Amazon in many countries as hardcover, paperback, and for your Kindle. (also on Leanpub). And all my German readers can get the German edition in every book store.

Ute Eberle, “Gefahr Ist Gut,” Zeit, 2005, https://www.zeit.de/zeit-wissen/2005/05/Verkehrsberuhigung_NEU.xml.

Stephen Johnson, “Want Less Car Accidents? Remove Traffic Signals and Road Signs,” Big Think, August 31, 2017, https://bigthink.com/the-present/want-less-car-accidents-get-rid-of-traffic-signals-road-signs/.

Viveka van de Vliet, “Space for People, Not for Cars,” Works That Work, 2013, 21.03.2022, https://worksthatwork.com/1/shared-space.

Tom McNichol, “Roads Gone Wild,” Wired, December 1, 2004, https://www.wired.com/2004/12/traffic/.

Laszlo Bock, Work Rules! Insights from inside Google That Will Transform How You Live and Lead, First published in paperback (London: John Murray, 2016), 365.

C. Northcote Parkinson, “Parkinson's Law,” The Economist 177, no. 5856 (November 19, 1955): 635–37.

Blaise Pascal and Lachmann, Friedrich Ludolf, Helwing, Christian Friedrich, Provinzialbriefe über die Sittenlehre und Politik der Jesuiten Theil 2, 1792, 263.

Paul Hoffman, Der Mann, der die Zahlen liebte: die erstaunliche Geschichte des Paul Erdös und die Suche nach der Schönheit in der Mathematik, trans. Regina Schneider (Berlin: Ullstein, 1999), 37.

Tom Meyvis and Heeyoung Yoon, “Adding Is Favoured over Subtracting in Problem Solving,” Nature 592, no. 7853 (April 8, 2021): 189–90, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00592-0; Gabrielle S. Adams et al., “People Systematically Overlook Subtractive Changes,” Nature 592, no. 7853 (April 2021): 258–61, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03380-y.

Joost Minnaar, “FAVI: How Zobrist Broke Down FAVI's Command-and-Control Structures,” Corporate Rebels, January 4, 2017, https://corporate-rebels.com/zobrist/.

Frédéric Laloux, Reinventing organizations: ein Leitfaden zur Gestaltung sinnstiftender Formen der Zusammenarbeit, trans. Mike Kauschke (München: Verlag Franz Vahlen, 2015), chap. 3.4.