Beyond Carrots and Sticks: Rethinking Motivation in Knowledge Work

Discover why traditional incentives may hinder creativity and collaboration among today's knowledge workers.

“The answer to the question managers so often ask of behavioral scientists, ‘How do you motivate people?’ is, ‘You don’t.’” In 1966, Douglas McGregor said everything you need to know about extrinsic motivation.

Nevertheless, more than fifty years later, many organizations still firmly believe in carrots and sticks in the form of financial incentive systems. After all, Peter F. Drucker, the great management thinker of the 20th century, proposed management by objectives (MbO) back in 1954, which is still more or less standard today. Unfortunately, one tiny detail of his actual good idea has been forgotten or ignored: The respective chapter in his book is titled “Management by Objectives and Self-Control.”

Drucker coined the term “knowledge work” and repeatedly emphasized that knowledge workers must be managed fundamentally differently, namely at eye level, as we would say today: “Knowledge workers cannot be managed as subordinates; they are associates. They are seniors or juniors but not superiors and subordinates.” It was, therefore, clear to him that the problem of aligning companies to common goals could not simply be a matter of setting goals from above, reinforced by appropriate financial incentives to achieve them. He was concerned with leading with goals in the context of the self-direction of intrinsically motivated people. In the chapter on MbO, he even explicitly points out, backed up with several examples, how counterproductive financial incentives can be.

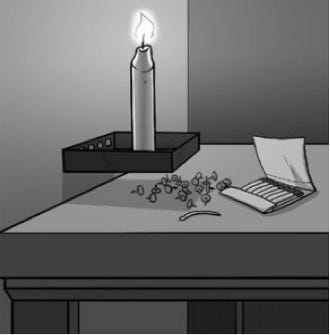

We are all well aware from practical experience that financial incentives can be detrimental to a shared focus. If these incentives would at least increase the performance of knowledge workers on an individual level, this misconfiguration of the target system could be eliminated. Yet, these incentives are even detrimental to knowledge work, as Sam Glucksberg demonstrated impressively in 1962. He combined the candle problem created by German psychologist Karl Duncker with a financial incentive and measured the participants’ performance in solving it.

In this experiment, the test subjects were given a candle, a pack of thumbtacks, and matches. The task was to attach the candle to the wall so no wax would drip onto the table. The solution requires cognitive skills insofar as one has to overcome the so-called functional fixation, which leads us to view the box with the thumbsticks merely as a container. Yet, the box can easily be attached to the wall using the thumbtacks and the candle placed into it. Gluckberg showed clearly, and it has been replicated repeatedly since then, that creative performance suffers considerably under the pressure of financial incentives: the test subjects took an average of 3.5 minutes longer to find the solution!

Evidence has been clear for decades. What hinders implementation?

References

Drucker, P. F. (1954). The practice of management (Nachdr.). HarperCollins.

Glucksberg, S. (1962). The influence of strength of drive on functional fixedness and perceptual recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 63(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044683

McGregor, D., & Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J. (2006). The human side of enterprise (Annotated ed). McGraw-Hill.

This newsletter is a personal project driven by my passion for agile methodologies and leadership. I believe we need to transform our organizations into more humane environments. I have been fortunate to sustain this initiative through the sales of my books in both German and English, as well as through the generous donations of my audience, for which I am incredibly grateful. If you would like to support Lead Like a Gardener and help it continue thriving without any ads, please consider making a small donation.

Donate Here → https://buymeacoffee.com/marcusraitner

Find more inspiration in my recently published “Manifesto for Humane Leadership.” Check it out on Leanpub.